- The global disease burden attributable to allergy and anaphylaxis continues to increase.

- This burden translates into significant personal costs to patients and families, and to overall healthcare costs.

- Early exposure to allergens may prevent the development of allergy later in life.

- For instance, the early introduction of peanuts into the diets of infants significantly decreased the frequency of the development of peanut allergy.

The hygiene hypothesis states that a lack of early childhood exposure to infectious agents, symbiotic microorganisms, parasites, drugs, and other allergens increases a person’s susceptibility to allergic diseases by suppressing the natural development of the immune system. The lack of exposure is thought to lead to defects in the establishment of immune tolerance. (See our related article here.)

This hypothesis suggests that the modern preoccupation with sterility and avoidance of exposure to microbes and allergens may in fact have precipitated an increase in the number of adults with allergies. Serious allergies and anaphylaxis can be life threatening. When less serious, allergies are costly to patients and to the healthcare system as a whole. Routine allergies, such as those to pollen (Figure 1) bee stings, peanut and other foods, drugs, latex and other substances can significantly detract from a patient’s quality of life.

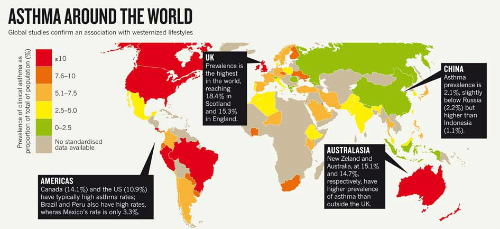

According to the hygiene hypothesis, the decreasing incidence of infections in Western countries, and more recently in developing countries, is at the origin of the increasing incidence of both autoimmune and allergic diseases, according to a review article published in Clinical & Experimental Immunology. “The hygiene hypothesis is based upon epidemiological data, particularly migration studies, showing that subjects migrating from a low-incidence to a high-incidence country acquire the immune disorders with a high incidence at the first generation,” (Figure 2) according to the authors of this review article.

Increasing Global Rate of Allergy

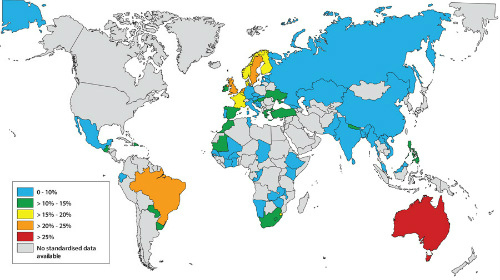

The global prevalence of food allergy appears to be rising, according to a review of systematic reviews published recently in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Increases in food allergy incidence have been reported in the United Kingdom, the U.S., and Australia where clinicians reported a 350% increase in hospital admissions for food-related anaphylaxis between 1994 and 2005, mostly among children and infants aged 0–4 years.

“Although the prevalence of food allergy is difficult to measure in the general population, the increasing global prevalence of food related anaphylaxis is likely to reflect an underlying increase in prevalence, which will add substantially to the food allergy health burden,” the reviewers wrote. “A point prevalence estimate in Australian children, from a unique population-based study using the gold standard of oral food challenge, suggests that the prevalence of infant food allergy might already be as high as 10% in a developed country urbanized setting.”

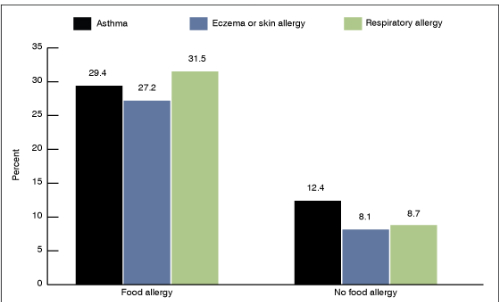

“Common immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated food allergies (Figure 4) in early life include: cow’s milk, hen’s egg, and peanut. Most IgE-mediated egg and milk allergies resolve over the first few years. By contrast, peanut allergy, which is more commonly associated with more severe reactions and a higher risk of anaphylaxis, is less likely to resolve, with only 20% of infants outgrowing their peanut allergy by the age of 5 years. The apparent increases in infant food allergy prevalence may result in an increase in adulthood food allergy. It has also been proposed that food allergy may be the first step of the allergic march leading to asthma and hay fever. These consequences of food allergy put the increasing health burden into better perspective.,” they concluded.

The Link Between Gut Microbiota, Disease, and Allergy

The increase in allergic diseases over the past several decades is correlated with changes in the composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota, according to a recent review article published in Clinical Immunology. “Microbial-derived signals are critical for instructing the developing immune system and conversely, immune regulation can impact the microbiota. Perturbations in the microbiota composition may be especially important during early-life when the immune system is still developing, resulting in a critical window of opportunity for instructing the immune system.”

“Diseases that appear to be impacted by alterations in the microbiota or linked to dysbiosis include metabolic diseases, autoimmunity, inflammatory diseases, neurological diseases, and allergy,” the authors wrote, citing a 2013 review article published in Current Opinions in Immunology.

The American Gut Project and Dysbiosis

Alteration of the gut microbial population (dysbiosis) may increase the risk of allergies and other conditions, according to the results of a study published recently in EBioMedicine. The study included an analysis of data from the American Gut Project. (See our related article here.)

Fecal microbiota richness (number of observed species), diversity, and composition were used to compare adults with and without allergies to foods (peanuts, tree nuts, shellfish, and others), as well as non-food allergies (drug, bee sting, dander, asthma, seasonal, eczema). (Figure 5.) Fecal microbiota richness was markedly lower among participants who reported total allergies (P=10 [-9]) and 5 particular allergies (P≤10 [-4]). Richness odds ratios were 1.7 (CI 1.3-2.2) among participants who reported seasonal allergies, 1.8 (CI 1.3-2.5) among those who reported drug allergies, and 7.8 (CI 2.3-26.5) among those with peanut allergy.

Preventing Peanut Allergy through Early Consumption

When it comes to peanut allergy, avoidance has failed and early exposure shows promise for preparing young immune systems to deal effectively with peanut-borne allergens. In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that parents not feed peanuts to children aged <3 years. However, between 2000 and 2010, the prevalence of peanut allergy in the United States more than quadrupled, rising from 0.4% in 1997 to more than 2% in 2010. Peanut allergy has become the leading cause of anaphylaxis and death related to food allergy in the U.S., according to a recent editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine. The authors of this editorial recommend preventing peanut allergy through early consumption of peanuts.

Randomized Trial of Peanut Consumption in Infants

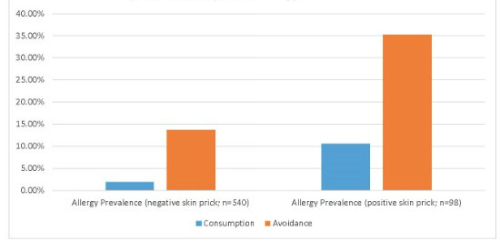

George Du Toit, MB, BCh, et al, and the multicenter Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study group conducted a randomized trial of avoidance versus exposure for the prevention of peanut allergies in infants and children (Figure 6).

of allergy versus those who avoided peanuts.

The LEAP group randomly assigned 640 infants with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both to either consume or avoid peanuts until they reached age 5 years. Children who were ≥4 months but ≤11 months of age at the time of randomization were assigned to separate study cohorts on the basis of preexisting sensitivity to peanut extract. The primary outcome was the proportion of participants with peanut allergy at age 5 years.

Among the 530 children who had initial negative results on the skin-prick test, the prevalence of peanut allergy at age 5 years was 13.7% in the avoidance group and 1.9% in the consumption group (P<0.001), the researchers reported.

Among the 98 participants in the intention-to-treat population, those who had initial positive test results, the prevalence of peanut allergy was 35.3% in the avoidance group and 10.6% in the consumption group (P=0.004). (Figure 6.)

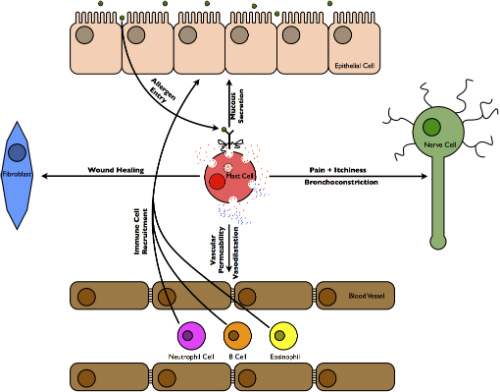

There was no significant between-group difference in the incidence of serious adverse events between the 2 groups. Increases in levels of peanut-specific IgG4 antibody occurred predominantly in the consumption group. However, a greater percentage of participants in the avoidance group had elevated titers of peanut-specific IgE antibody.(Figure 7.)

Figure 7. Tissues affected in allergic inflammation.

The LEAP investigators concluded that the early introduction of peanuts into the diets of these infants significantly decreased the frequency at which peanut allergy developed. This finding held even among children at high risk for this allergy.