- High fat (or negative) emotions are draining; they can heighten the perception of pain.

- Low fat (or positive) emotions are energizing; they can decrease the perception of pain.

- High stress-low reward experiences lead to a diet heavy in high fat (negative emotions) and lead to psychological undernourishment. Alternatively, low-stress, high-reward diets are rich in positive emotions and can lead to a psychologically nourishing state.

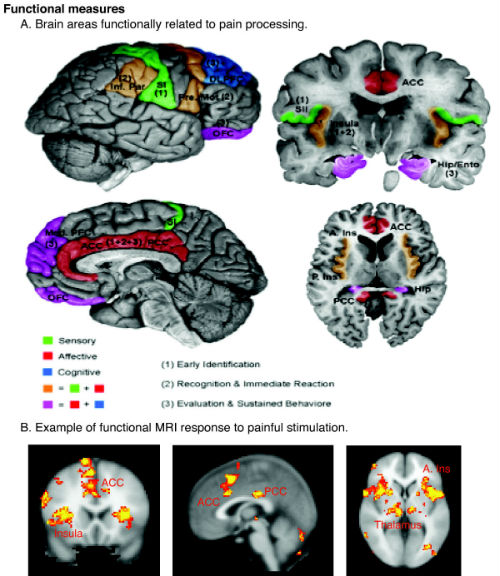

Any physician who cares for patients with chronic pain knows that analgesia—by any means necessary—is the patient’s primary desire. This clinical outcome is often difficult to achieve, especially for chronic pain patients. Over the long term, pain and emotion become intertwined (Figure 1).

_and_a_face_cropped.jpg)

(Sources: Charles Le Brun; John Tinney;

Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust,

a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom.

(Refer to Wellcome blog post [archive].)

Chronic physical pain causes emotional pain; which, ironically, can lead to hyperalgesia. The patient becomes more sensitive to pain without any obvious change in pain stimuli. The debilitating effects of chronic pain span physical, emotional, social, and occupational functioning (Figure 2). In a report published in 2014, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Disease Prevention estimated that chronic pain affects more than 30%—about 100 million—Americans. It has a high financial cost as well in the form of lost work efficiency and effectiveness as well as high medical costs. The dollar cost was estimated by the NIH to be $560 to $630 billion per year.

(Sources: Wikipedia/Borsook/Creative Commons

(© 2007 Borsook et al; Licensee: BioMed Central Ltd.)

Opioids and Chronic Pain

Opioids are often effective for short-term analgesia in cases of acute pain. However, the long-term use of opioids has proven to be problematic. For example, the long-term use of opioids may produce a chronic pain state, may lead to dependence, addiction, and abuse, and may cause emotional depression. Moreover, the side-effects of opioids alone, or in combination with other drugs (prescribed or illicit), or if misused by patients with co-morbid conditions such as sleep apnea, can lead to impairing sedation, respiratory depression, liver damage, or death, for example.

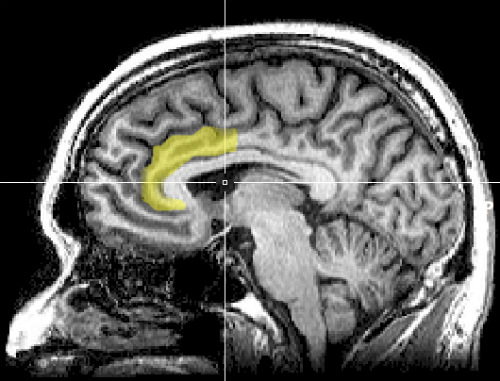

For these reasons, pain-management specialists have developed alternatives to opioids for pain management of chronic pain. These include approaches that focus on psychosocial factors, including psychotherapy (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy to address disordered thinking, mindfulness treatment to reframe the experience of pain, and acceptance commitment therapy to augment psychological flexibility). (Figure 3.) Other strategies include meditation, yoga, aromatherapy, and acupuncture. Some of these, such as yoga, have been demonstrated to be effective in clinical trials. These modalities have gained prominence as therapies that are complementary to traditional medical interventions. These methods have support in the form of small to moderate effect sizes in meta-analytic studies.

(Sources: Wikipedia/Creative Commons.)

Despite the potential negative effects of chronic opioid use, opioids remain widely used in the management of chronic pain. In part, this may be because patients are simply not receptive to discussion non-pharmacologic interventions. It may also be related the time-starved environment in which many clinicians work. You simply don’t have the time to discuss these options with your patients.

Recommending non-opioid treatment may: 1) Signal to the patient that his or her pain condition is hopeless; 2) It may exacerbate the patient’s emotional distress; 3) It may suggest to the patient that you believe he or she is abusing opioids; and 4) It may suggest that you distrust the patient’s reports of the severity of the pain.

Is there a way that you can begin the discussion of alternate treatments that avoid a defensive reaction by the patient? We suggest that reframing pain management as the management of emotional, or psychological nutrition may be one such method.

Psychological Nutrition

We have developed the concept of psychological nutrition. We have made it readily accessible and intuitive. It adopts terminology and concepts of pain with which patients are familiar but translates them into the terminology seen on nutritional labels for food products. We then apply them to emotions. Psychological reactions are conceptualized from the unique perspective that emotions are dietary ingredients.

Today, many people are concerned about eating a healthy diet. They may examine the ingredients of the food they eat to find out whether it’s high or low in fat, sodium, calories, fiber, etc., before they buy or eat it. Yet, people are not as attuned to assessing whether their interactions with certain people or their experiences with certain situations or phenomena may be emotionally nutritious for them. Consequently, many pain patients consume a diet of unhealthy emotions without realizing it.

An emotional diet that is high in fat, so to speak—full of negative emotions—is not healthy. It drains the patient of emotional energy and resiliency and lead to feelings of anger, bitterness, fear, depression, and hopelessness. Whereas a low-fat, nutritious emotional diet is augments emotional energy and reinforces a positive sense of self. Just as there is junk food, there are junk emotions.

Why Would Understanding One’s Emotional Nutritional Intake

Help Manage Chronic Pain?

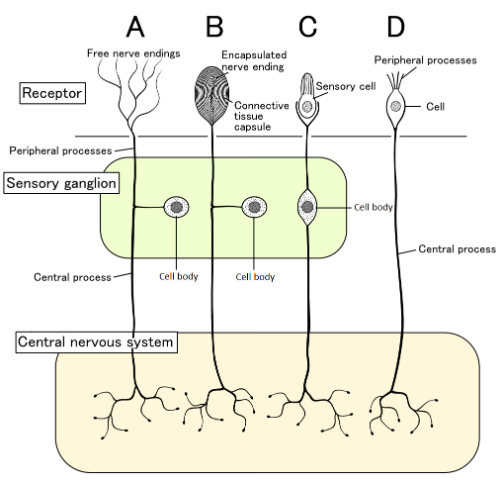

Chronic pain is associated with the activation of brain centers related to the interpretation of pain (the pre-frontal cortex) and emotion (the limbic system). Thereby, the concept of emotional nutrition provides the why of how emotional reactivity and cognitive mindsets can change one’s experience of pain.

Self-management strategies where in which the patient reframes the thoughts and feelings about pain may actually bring about changes in neural activity (such as reducing activity in the amygdala linked to anxiety and stress responses) can in turn help decrease the perception of pain. Understanding how negative emotional states increase the perception of pain intensity is another aspect of pain literacy and is a self-management strategy. These concepts provide the basis of psychological nutrition:

- High fat (or negative) emotions are draining; they can heighten the perception of pain.

- Low fat (or positive) emotions are energizing; they can decrease the perception of pain.

- High stress-low reward experiences lead to a diet heavy in high fat (negative emotions) and lead to psychological undernourishment. Alternatively, low-stress, high-reward diets are rich in positive emotions and can lead to a psychologically nourishing state.

- Developing a snapshot of one’s day—the ratio of high-fat to low-fat emotions can provide the patient with an understanding of whether he or she is in an emotionally nourished or malnourished state.

Pain causes emotional distress and in turn emotional distress heighten the perception of pain which then heightens the patient’s suffering. Therefore, understanding the cyclical nature of how emotional responses affect the perception of pain is clinically valuable. For example, the more one focuses on the pain, the greater the intensity of the pain perception. This is turn leads to psychologically non-nutritious (high-fat) emotions such as stress, fear, frustration, helplessness, hopelessness, and depression. (Figure 4.)

(Sources: Wikipedia/Creative Commons.)

Psychological Nutritional Prescription for Pain Reduction

The initial step of initiating a psychologically nutritious pain state consists of a quality-of-life assessment. This helps the patient and the physician better understand which events and experiences contribute to the patient’s psychological nutrition or malnutrition. Once the patient understands this, the she or he will be better prepared for the following:

- To receiving education and information about the medical condition causing the pain and the nature of the pain experience. Education and information can reduce the patient’s anxiety and thereby reduce the severity of the pain experience

- To developing self-efficacy that he or she can exert to control the pain experience. Just as people can control their nutritional intake of food, patients can control their psychological nutritional emotions.

- To recognize negative emotional reactions (high fat) to pain (such as fear and depression) and how these emotions can be regulated so that the patient focuses less on the negative and increase the intake of positive emotions (low fat; such as spending more time on and being more preoccupied with thoughts and activities that do not center on pain; engaging in fun or spiritual activities).

- To emphasize stress management, coping skills, and relaxation. If the pain cannot be reduced entirely, its sensation can be diminished if the patient learns better adaptation strategies.

- To join a pain support group. Just as there are support groups to help people modify diet and lose weight, the patient should be encouraged to attend pain support groups. Sharing with people who have similar problems may feel more authentic for the patient and can help modify the emotional amplification of the pain.

Periodically, the patient should reassess his or her quality of life and level of psychological nutrition. As the emotional diet improves, so should the experience and reaction to pain. Psychological nourishment means living a meaningful life, one that places pain in the background rather than the foreground.

Shoba Sreenivasan, PhD, and Linda E. Weinberger, PhD, are the authors of the new book Psychological Nutrition, which encourages patients to live happier and healthier lives by monitoring emotions that are consumed on a daily basis.