- Poor sleep habits significantly increase the risk of overweight and obesity.

- Poor sleep also induces neurocognitive dysfunction.

- Stimulant medications disrupt sleep in youth and adolescents.

- Statin therapy was not found to adversely affect sleep quality.

Poor sleep habits can be significantly deleterious for patients and are linked with a wide variety of diseases and disorders. While sleep is trivialized in some contexts – among physicians and soldiers for instance – scientific researchers have shown us beyond reasonable doubt that sleep deficiency is dangerous.

Maintaining good sleep hygiene should be one of the things you talk about with your patients when you have the conversation about dangerous situations that can be easily mitigated – such as improved eating habits, exercise, adherence to prescription medication directions, increased social connections, and maintaining a healthy body weight.

Teaching your patients to sleep well could prevent the occurrence of a multitude of diseases and disorders.

Click here to read our recent article on sleep, sleep hygiene, and sleep-related disorders.

Following is a brief review of the recent literature on sleep:

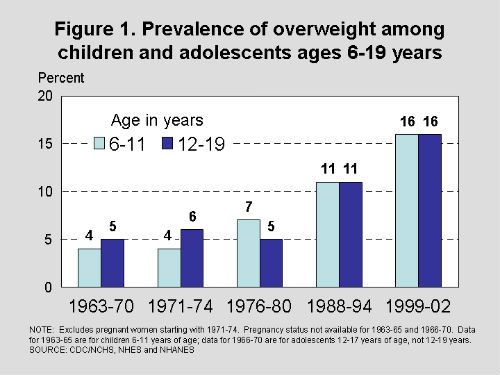

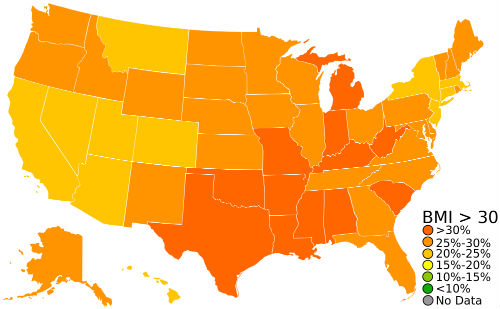

1. Children with Short Sleep Duration 75% more Likely to be Overweight

A systematic review published recently in Scientific Reports, an online, open access journal from the publishers of Nature, found that shorter-time sleep was correlated with increased risk of obesity in children.

This meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies found that shorter-time sleep was linked with increased risk of obesity in children. The researchers identified 25 studies including 56,584 children and adolescents with an average 3.4-year follow-up.

Compared with children having the longest sleep duration, kids with the shortest sleep duration were 76% more likely to be overweight/obese; and had relatively larger annual BMI gain, the researchers reported. With every 1 hour/day increment in sleep duration, the risk of overweight/obesity was reduced by 21%; and the annual BMI gain declined by 0.05 kg/m2.

“Accumulated literature indicates a modest inverse association between sleep duration and the risk of childhood overweight/obesity,” the researchers concluded.

2. The Influence of Sleep Duration and Sleep-Related Symptoms on Baseline Neurocognitive Performance Among Male and Female High School Athletes

A recent study of sleep habits in more than 7000 high school athletes was conducted by Alicia Sufrinko and her team and published electronically in Neuropsychology. This latest piece of research was designed to examine the effects of sleep duration on cognition among high school athletes. Specifically, the study examined the effects of restricted sleep and related symptoms on neurocognitive performance.

To begin, the researchers administered a Baseline Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing (ImPACT) and postconcussion symptom scale (PCSS) to all athletes (N=7,150) ages 14-17 (M=15.26, SD=1.09) prior to sport participation. Three groups of athletes were derived from total sleep duration: sleep restriction (≤5 hours), typical sleep (5.5-8.5 hours), and optimal sleep (≥9 hours). A MANCOVA (age and sex as covariates) was conducted to examine differences across ImPACT/PCSS. Follow-up MANOVA compared ImPACT/PCSS performance among symptomatic (e.g., trouble falling asleep, sleeping less than usual) adolescents from the sleep restriction group (n=78) with asymptomatic optimal sleepers (n=99).

The researchers found a dose-response effect of sleep duration on cognition as measured by followup ImPACT performance and PCSS scores (P < .001. The symptomatic sleep restricted adolescents (n=78) had poorer neurocognitive performance: verbal memory, F=11.60, P=.001, visual memory, F=6.57, P=.01, visual motor speed, F=6.19, P=.01, and reaction time (RT)=5.21, P=.02, compared to demographically matched controls (n=99). Girls in the sleep problem group performed worse on RT (P=.024).

“Examining the combination of sleep-related symptoms and reduced sleep duration effectively identified adolescents at risk for poor neurocognitive performance than sleep duration alone,” the researchers reported.

3. The most recent guidance from the Agency, Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, in Madrid, Spain categorizes sleep recommendations by the quality of the evidence supporting those recommendations.

Spain’s Guideline Development Group on Sleep Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence in Primary Care has issued its “Clinical practice guideline on sleep disorders in childhood and adolescence in primary care” through Spain’s Health Technology Assessment Unit, Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Click here for the entire guidelines.

While many of this group’s findings were equivocal, a number of psychologic interventions were found to be effective for insomnia among children and adolescents:

B - Techniques based on the principles of behavioral therapy (BT) for insomnia should at least include graduated extinction, after parent education. Other behavioral therapies that can be recommended are unmodified extinction, delaying bedtime in conjunction with the pre-sleep ritual and scheduled awakenings.

Good clinical practice point - Before recommending the graduated extinction technique, it is recommendable to assess the parent's tolerance to this technique, for which a series of questions can help (see Appendix 12 in the original guideline document).

B - For adolescents, sleep hygiene practices and behavioral interventions that at least include stimulus control is recommended for treating insomnia. Another intervention that could be recommended is cognitive restructuring.

B - For adolescents, sleep education and management programmes are recommended, including guidelines on sleep hygiene practices, instructions on stimulus control and information about consuming substances and the impact that sleep problems can have on mood and academic performance.

B - To reduce cognitive activation prior to sleep in adolescents who have insomnia and a tendency to think about their problems when it's time to go to bed, a structured problem-solving procedure is recommended.

4. Stimulant Medications and Sleep for Youth With ADHD: A Meta-Analysis

This meta-analysis found that many youth and adolescents suffer from suboptimal sleep as a result of the abuse of stimulant medications.

The researchers evaluated 9 studies that included 246 subjects. For sleep latency, the adjusted effect size was significant, indicating that stimulants produce longer sleep latencies. Frequency of dose per day was a significant moderator.

For sleep efficiency, the adjusted effect size was significant. Significant moderators included length of time taking the medication, number of nights of sleep assessed, polysomnography/actigraphy, and gender.

“Specifically, the effect of medication was less evident when youth were taking medication for longer periods. For total sleep time, the effect size (-0.59) was significant, such that stimulants led to shorter sleep duration,” the authors wrote.

“Stimulant medication led to longer sleep latency, worse sleep efficiency, and shorter sleep duration. Overall, youth had worse sleep on stimulant medications. It is recommended that pediatricians carefully monitor sleep problems and adjust treatment to promote optimal sleep,”: they concluded

5. Sleep Changes Following Statin Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Polysomnographic Trials

The authors of a recent meta-analysis evaluated the effects of statin therapy on sleep. They reviewed the effect of statin therapy on polysomnography (PSG) indices of sleep as was reported in 5 trials comprising 9 treatment arms.

Overall, statin therapy had no significant effect on total sleep duration, sleep efficiency, entries to stage I, or latency to stage I, the researchers found.

In contrast, they wrote, statin therapy significantly reduced wake time and number of awakenings. Meta-regression did not suggest any correlation between changes in wake time and awakening episodes with duration of treatment and LDL-lowering effect of statins.

“The results indicated that statins have no significant adverse effect on sleep duration and efficiency, entry to stage I, or latency to stage I sleep, but significantly reduce wake time and number of awakenings,” the researchers concluded.