- About 1% of all cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are attributable to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- Approximately 15% of people who have alpha-1 antitrypsin disease have been diagnosed.

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is inherited as an autosomal-codominant condition.

- Blood tests are available to help clinicians distinguish COPD due to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency from COPD due to other causes.

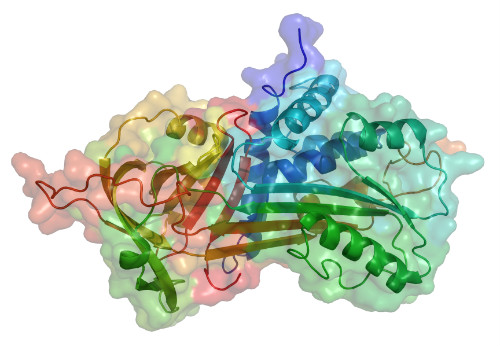

Alpha-1 antitrypsin (Figure 1) deficiency is a relatively common but under recognized cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), according to a review study published recently in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

(Sources: Wikipedia/Creative Commons/By own work [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.)

“Because delayed diagnosis is thought to be associated with adverse outcomes, clinicians are encouraged to follow available guidelines and test for the disease in all symptomatic adults with fixed airflow obstruction. The weight of available evidence supports the biochemical and clinical efficacy of intravenous augmentation therapy. Promising new therapies are being investigated,” wrote review author James, K. Stoller, MD, MS.

Dr. Stoller is the Chair of the Education Institute at Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio. He is also Head of Cleveland Clinic Respiratory Therapy in the Department of Pulmonary Medicine, and Professor at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

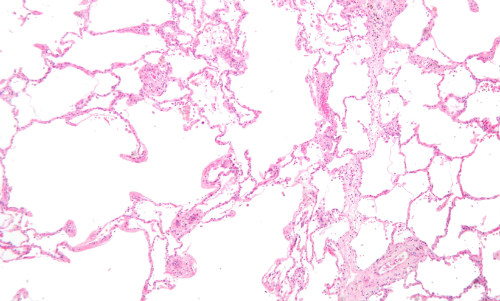

The basic care of a patient with COPD (Figures 2 and 3) due to alpha-1 antitrypsin disease is the same as for other cases of COPD. That typically includes “bronchodilators, inhaled steroids, supplemental oxygen, preventive vaccinations, and pulmonary rehabilitation as indicated. Specific treatment consists of weekly infusions of alpha-1 antitrypsin (augmentation therapy),” Dr. Stoller wrote.

(Sources: Wikipedia/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library/

By Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr. - Public Domain.)

and lung tissue with relative preservation of the alveoli (right).

Causes and Frequency

People with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency usually develop the first signs and symptoms of lung disease between ages 20 and 50, according to the website of the National Library of Medicine.

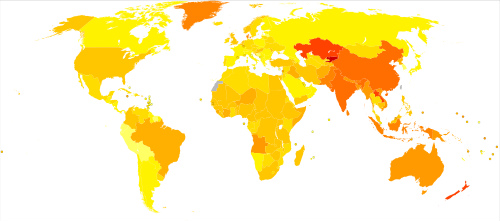

Approximately 1% of all cases of COPD (Figure 4) result from an alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, according to MayoClinic.org. The website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes that 8.7 million Americans were diagnosed with COPD in 2014. So about 87,000 of these cases could be attributable to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency annually. According to the World Health Organization website, about 64 million people worldwide had been diagnosed with COPD as of 2004; about 640,000 of these cases could be attributed to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

Diagnosing Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency

Available blood tests for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency include:

- Measurement of the serum alpha-1 antitrypsin level. This is most often measured by nephelometry. Normal serum levels generally range from 100mg/dL to 220mg/dL.

- Phenotyping. This is usually performed by isoelectric focusing, which can identify the band patterns associated with various alleles.

- Genotyping. This involves determining which alpha-1 antitrypsin alleles are present. Polymerase chain reaction testing is used to target the S and Z alleles. Less frequently it is used to detect such as F and I.

- Gene sequencing is occasionally necessary to achieve an accurate, definitive diagnosis.

- Free, confidential testing is available through the Alpha-1 Foundation. The foundation offers a free, home-based testing kit through a research protocol at the Medical University of South Carolina (alphaone@musc.edu). Patients can receive a kit and lancet at home, submit the dried blood-spot specimen, and receive in the mail a confidential serum level and genotype.

per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.

(Sources: Wikipedia/Creative Commons/By Lokal_Profil.)

Treatment of Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency-Related COPD

The treatment of patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency-related COPD and emphysema is generally similar to that of patients with COPD that results from other causes, such as smoking. Treatment includes smoking cessation, bronchodilators, inhaled steroids, supplemental oxygen, preventive vaccinations, and pulmonary rehabilitation.

“Lung volume reduction surgery, which is beneficial in appropriate subsets of COPD patients, is generally less effective in those with severe alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, specifically because the magnitude of FEV1 increase and the duration of such a rise are lower than in usual COPD patients,” Dr. Stoller explained.

Augmentation Therapy

Specific therapy for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency currently involves weekly intravenous infusions of purified, pooled human-plasma-derived alpha-1 antitrypsin, so-called augmentation therapy,” noted Dr. Stoller. The FDA has approved 4 brands of alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor (human) for use in the U.S. They are:

- Prolastin-C (Grifols, Barcelona, Spain)

- Aralast NP (Baxalta, Bonneckborn, IL)

- Zemaira (CSL Behring, King of Prussia, PA)

- Glassia (Baxalta, Bonneckborn, IL, and Kamada, Ness Ziona, Israel)

Infusion of these drugs has been shown to raise alpha-1 antitrypsin serum levels “above a protective threshold value (generally considered 57mg/dL, the value below which the risk of developing emphysema increases beyond normal,” Dr. Stoller explained.

The evidence behind the clinical use of alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor is not particularly strong. “Randomized controlled trials have addressed the efficacy of intravenous augmentation therapy, and although no single trial has been definitive, the weight of evidence shows that augmentation therapy can slow the progression of emphysema,” wrote Dr. Stoller.

Nonetheless, the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society have recommended augmentation therapy in individuals with “established airflow obstruction from alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.” The guidelines state that the evidence supporting the use of augmentation therapy as beneficial is stronger for individuals who have moderate airflow obstruction (eg, FEV1 35% to 60% of predicted) than it is for those whose airflow obstruction is severe. Augmentation therapy is not recommended for patients who do not have emphysema, according to the guidelines