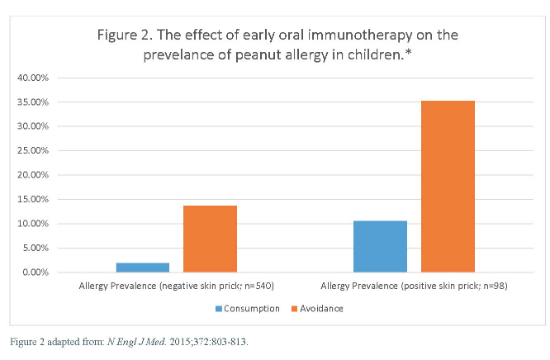

- The prevalence of peanut allergy at 5 years of age was 13.7% in the avoidance group and 1.9% in the consumption group (P<0.001).

- Exposure is proving to be more effective than avoidance in preventing skin and food allergies.

- During the period of peanut avoidance in young children–2000 to 2010–the prevalence of peanut allergy more than quadrupled.

- Do these findings explain the rural-urban enigma of allergy?

Childhood asthma and related allergic conditions have become the most common chronic disorders in the Western world, according to a recent article in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology (2015;18 Feb:DOI:10.1111/pai.12341). An increasing number of studies suggest that early exposure to allergens as oral immunotherapy may be the most effective and cost-effective way to control some childhood allergies.

Avoidance Has Failed

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that parents not feed peanuts to children younger than age 3 years. However between 2000 and 2010, the prevalence of peanut allergy in the United States more than quadrupled from 0.4% in 1997 to more than 2% in 2010. Peanut allergy has become the leading cause of anaphylaxis and death related to food allergy in the U.S., according to an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine (2015;372:875-877). (See Figure 1.) The medical community has tried recommending allergen avoidance, and it has not been shown to work, certainly when it comes to peanuts. (See our brief literature review on oral immunotherapy.)

The LEAP group randomly assigned 640 infants with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both to either consume or avoid peanuts until the children were aged 5 years. Children who were ≥4 months but ≤11 months of age at the time of randomization were assigned to separate study cohorts on the basis of preexisting sensitivity to peanut extract. The primary outcome was the proportion of participants with peanut allergy at age 5 years.

Exposure-Prevention in Ready for Prime Time

The authors of the New England Journal of Medicine editorial ask whether “preventing peanut allergy through early consumption” is “ready for prime time.” While there has been anecdotal evidence that early oral immunotherapy can prevent food allergies, no randomized, controlled trial had been completed until the recent publication by Du Toit and the multicenter Learning Early about Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study group (N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-13).

The LEAP group randomly assigned 640 infants with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both to either consume or avoid peanuts until the children were aged 5 years. Children who were ≥4 months but ≤11 months of age at the time of randomization were assigned to separate study cohorts on the basis of preexisting sensitivity to peanut extract. The primary outcome was the proportion of participants with peanut allergy at age 5 years.

Among the 530 children who had initial negative results on the skin-prick test, the prevalence of peanut allergy at age 5 years was 13.7% in the avoidance group and 1.9% in the consumption group (P<0.001), the researchers reported.

Among the 98 participants in the intention-to-treat population, those who had initial positive test results, the prevalence of peanut allergy was 35.3% in the avoidance group and 10.6% in the consumption group (P=0.004). (See Figure 2.)

There was no significant between-group difference in the incidence of serious adverse events between the two groups. Increases in levels of peanut-specific IgG4 antibody occurred predominantly in the consumption group. However, a greater percentage of participants in the avoidance group had elevated titers of peanut-specific IgE antibody.

The LEAP investigators concluded that the early introduction of peanuts into the diets of these infants significantly decreased the frequency of the development of peanut allergy. This finding held even among children at high risk for this allergy.

Does Exposure = Prevention?

One of the most common and consistent epidemiologic findings in international studies of childhood allergies has been that children living in rural areas experienced a decreased incidence of allergies when compared to those who were raised in urban areas, according to a review article in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology (2015 Jan 24. doi: 10.1111/pai.12341). Indeed, this international phenomenon has come to be known among researchers as the rural-urban enigma of allergy.

Two recent studies from Sweden suggest further support for this exposure hypothesis. Both studies were published in Pediatrics and were conducted by group in Gothenburg, Sweden, headed by Bill Hesselmar, MD, PhD.

Dishwashing

"We have only tested an association between dishwashing methods and risk of allergy,” Dr. Hesselmar explained. “But the findings fit well with the hygiene hypothesis. There are studies showing that hand dishwashing very often is less effective than machine dishwashing in reducing bacterial content. We therefore speculate that hand dishwashing is associated with increased microbial exposure, causing immune stimulation and, hence, less allergy,” said Dr. Hesselmar, Associate Professor of Allergy at Queen Silvia Children's Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden.

In this case, Hesselmar, et al, conducted a questionnaire-based study of 1029 children aged 7 to 8 years. A portion of the children lived in Kiruna, in the north of Sweden, and a portion lived in the Gothenburg area on the southwest coast of Sweden. The study was published in Pediatrics (2015;135:e590-e597).

Questions on asthma, eczema, and rhinoconjunctivitis were taken from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire.

The researchers found that hand dishwashing was associated with a reduced risk of allergy (odds ratio 0.57; 95% confidence interval: 0.37–0.85). The risk was further reduced in a dose-response pattern if the children were also served fermented food and if the family bought food directly from farms.

“In families who use hand dishwashing, allergic diseases in children are less common than in children from families who use machine dishwashing. We speculate that a less-efficient dishwashing method may induce tolerance via increased microbial exposure,” the authors concluded.

Clean the Pacifier by Mouth

The group led by Dr. Hesselmar published an interesting study in Pediatrics in 2013 that further suggests the strength of the hygiene hypothesis (Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1829-37). In this case, Hesslemar et al showed that children whose parents cleaned the pacifier by mouth were significantly less likely to develop asthma, eczema, or atopy than were children whose parents boiled the pacifier to clean it.

This group studied 184 infants who were examined for allergy and sensitization at 18 months and 3 years of age. While boiling had no effect on the development of allergies, cleaning the pacifier by mouth, as well as other factors, contributed to significantly reduced rates of food and skin allergies. Vaginal birth conferred further immunologic benefit.

“Children whose parents ‘cleaned’ their pacifier by sucking it (n=65) were less likely to have asthma (odds ratio [OR] 0.12; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.01–0.99), eczema (OR 0.37; 95% CI 0.15–0.91), and sensitization (OR 0.37; 95% CI 0.10–1.27) at 18 months of age than children whose parents did not use this cleaning technique (n=58). Protection against eczema remained at age 3 years (hazard ratio 0.51; P=0.04),” the authors wrote.

More than 9000 Chinese Schoolchildren

These two studies can be interpreted as building upon the work of earlier groups. In one case, a 2009 study found a very low prevalence of asthma and allergies among more than 9000 schoolchildren from rural Beijing, China. The study was published in Pediatric Pulmonology (2009;44:793-9. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21061).

“There is consistent evidence that growing up on a farm is associated with protection against the subsequent development of asthma,” the authors wrote.

Children were randomly selected from samples of schoolchildren aged 13-14 years from either urban Beijing or the rural area around Beijing. They were assessed using the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase III protocol. The children were studied either by questionnaire (n=7077) or skin-prick test (n=2126).

The prevalence of wheeze in the past year and physicians' diagnosis of asthma were 1.0% and 1.1% in the rural area, the researchers reported. These prevalences were significantly lower than the 7.2% and 6.3% found in the urban children (P<0.0001). Atopy was 3.22 times more common in urban children than in rural children (P<0.0001).

“Using the same validated ISAAC questionnaire and objective skin-prick tests, the prevalence rates of asthma and atopic sensitization in rural Chinese children were significantly lower than urban children. Exposure to agricultural farming conferred the same protection as livestock farming,” the authors wrote.

More Than 10,000 Bavarian Schoolchildren

A 2000 study in Clinical and Experimental Allergy (2000;30:187-93). Found a reduced risk of hay fever and asthma among the children of farmers.

This was a cross-sectional survey study that included 10,163 children entering school (aged 5-7 years). A written questionnaire including the ISAAC core questions and asking for exposures on a farm and elsewhere was administered to the parents during school health entry examination in two Bavarian districts with extensive farming activity.

The main outcome measure was the prevalence of doctors’ diagnoses and symptoms of hay fever, asthma and eczema as assessed by parental report. The researchers found that the children of farmers had lower prevalences of hay fever, asthma, and wheeze when compared with children who did not live in an agricultural environment.

“The reduction in risk was stronger for children whose families were running the farm on a full-time basis as compared with families with part-time farming activity. Among farmers' children increasing exposure to livestock was related to a decreasing prevalence of atopic diseases,” the researchers wrote.