Click here for the next article in the series.

According to data from the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) Lung Cancer Staging Project, the 5-year survival rates after complete surgical resection are 73% for stage IA, 58% for stage IB, 46% for stage IIA, 36% for stage IIB, and 24% for stage IIIA.3 The majority of cases of recurrent lung cancer are characterized by distant metastases with locoregional recurrence; other cases may have distant metastases alone (oligometastases) or locoregional recurrence alone.4

The overall incidence of locoregional or advanced-stage recurrent lung cancer is approximately 33%, with a median time of 11.5 months to recurrence.5 Factors that independently predict outcome after surgical resection of early-stage NSCLC include sex, staging, vascular endothelial growth factor score, and percent nuclear cyclin D1 expression.6 In patients with advanced, unresectable disease, recurrence is usual, with a median survival time of 8 to 11 months.7

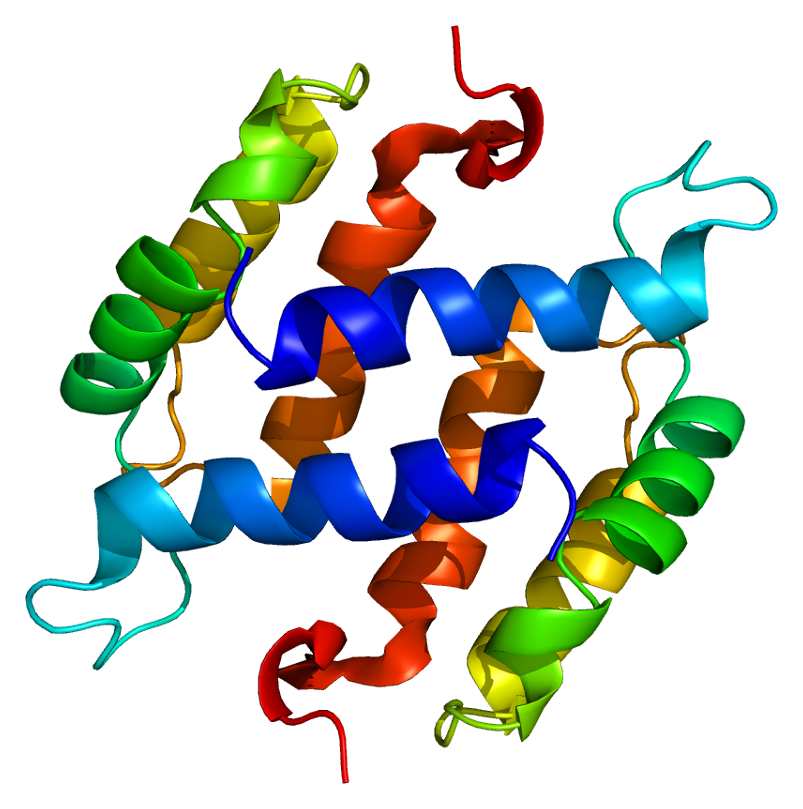

Extracellular S100 proteins have been shown to exert regulatory effects on inflammatory cells, neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and endothelial and epithelial cells.21 Dysregulated expression of multiple members of the S100 protein family is a common feature of human cancers. Due to the regulatory effects of the S100 protein family, each type of cancer will have a unique S100 protein profile or signature. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Structure of the S100B protein.

Signs of Recurrence

The approach to second-round care is often multidisciplinary, typically involving specialists in thoracic medicine, surgery, and radiation oncology; interventional radiology; pathology; and pulmonology. Specialist nurses may also provide care.

The early initiation of palliative care has been shown to have important benefits in patients with recurrent NSCLC. A randomized trial by Temel et al. demonstrated that patients receiving early palliative care had higher quality-of-life scores, had a more positive outlook, underwent less aggressive end-of-life care, and enjoyed longer median survival times compared with those receiving standard care alone.9 Multidisciplinary care models may facilitate the integration of palliative care into routine clinical care.10

Management of Recurrence

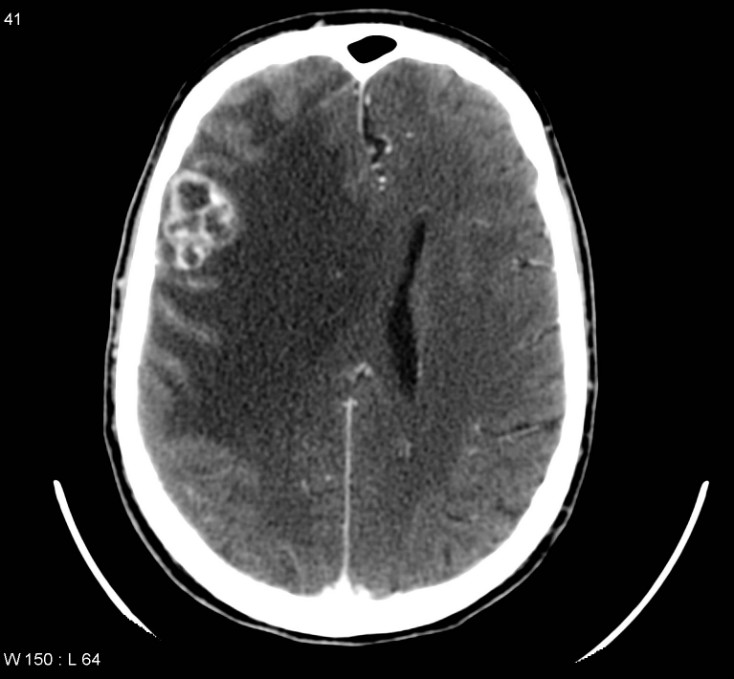

Most trials have evaluated cisplatin-containing doublets. Both taxanes and folate antimetabolites have been found to improve survival in patients with distant recurrences compared with supportive care alone.11 Local administration has been used successfully in patients who have oligometastases isolated to the brain or adrenal glands, with stereotactic radiotherapy a well-accepted standard for those who have limited brain metastases.12 Locoregional recurrent disease, defined as disease limited to the ipsilateral hemithorax and mediastinum excluding pulmonary lesions, is treated surgically in selected patients or with concurrent chemoradiotherapy.4

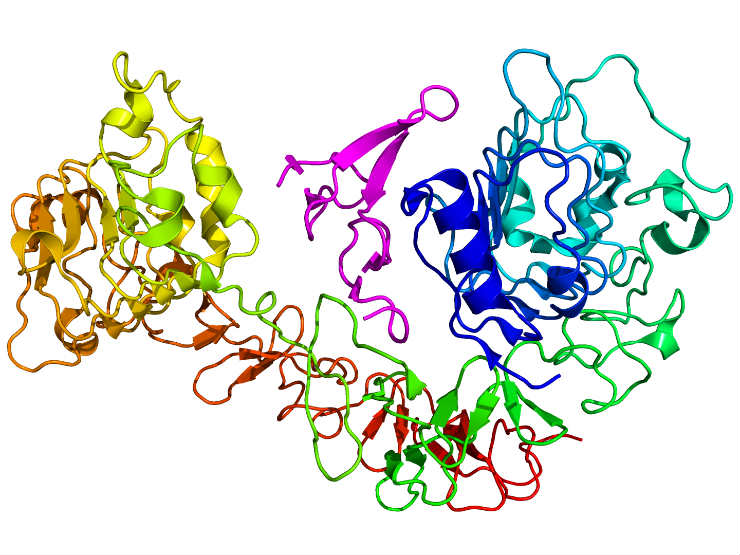

Modern chemotherapy (biologic). The approaches to advanced lung cancer have changed with the advent of newer targeted therapies.13 (See Figure 3.) The discovery of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion in adenocarcinoma-type NSCLC heralded the development of novel agents targeting these molecules. This progress has been enabled by the recognition that different molecular characteristics drive tumor biology and clinical responsiveness 14 and is reflected in the updated National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.15

Second-Round Prognosis

Survival. The location of recurrences, as well as the nature of the primary medical approach, affect the prognosis of patients with recurrent disease.4 ECOG performance status, length of the disease-free interval, presence of signs, and location of the recurrence have been identified as factors independently predicting survival after recurrence.5 A retrospective study of patients with distant metastases alone found that adenocarcinoma histology, a disease-free interval of 1 year or longer, and the use of local agents predicted post-recurrence survival.16

More recently, no adjuvant chemotherapy for the primary lung cancer and wild-type EGFR were associated with decreased post-recurrence survival.8 Early studies found post-recurrence survival rates of 15% to 20%, with a median survival time of 8 to 13 months. In contrast, Saisho et al. described a post-recurrence 2-year survival rate of 45.8%, with a median survival time of 17.7 months. Observed differences in post-recurrence survival may reflect the evolution of care toward newer agents, including EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).8

Quality of life. The goals in recurrent NSCLC are directed toward improving both survival and quality of life. Patient considerations regarding dosing, administration, and tolerability affect decisions regarding pharmacologic choices.7,17 Advanced age and medical comorbidities are commonly associated with recurrence and present unique quality-of-life considerations. Adverse events have been shown to have a significant negative influence on quality of life,18 emphasizing the need for the continued development of precision agents with favorable profiles for both efficacy and tolerability.

Influence of Accountable Care Organization Models

In Patients for whom First Line has Failed

New models of healthcare delivery may influence the delivery of second-round care to patients for whom first-round care has failed. Global payment systems for second-line chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery will encourage outcomes-based research to identify strategies that offer the greatest benefit on survival and quality of life at the lowest cost. The multidisciplinary approach to recurrent NSCLC is in alignment with data collection and care coordination goals inherent to the performance-based medicine and accountable care models.19

The technological evolution toward molecular biological approaches is associated with increased costs, a point of focus for accountable care organizations (ACOs). Although coordinated care and shared decision making are theorized to lead to improves quality of care at lower cost, outcomes evidence specific to lung cancer is lacking. Preliminary reports of the oncology patient-centered medical home describe improvements in several operational and clinical variables in a community oncology system.20 Further research to develop analytic measures specifically for NSCLC – reflecting advances in genomics, personalized diagnosis, and novel protocols – will be needed to further elucidate the role of the ACO model in both primary and recurrent NSCLC.References

- Herbst RS, Heymach JV, Lippman SM. Lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(13):1367-1380.

- Teixido C, Karachaliou N, Gonzalez-Cao M, Morales-Espinosa D, Rosell R. Assays for predicting and monitoring responses to lung cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12(2):87-95.

- Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer International Staging Committee; Participating Institutions. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumors. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(8):706-714.

- Yano T, Okamoto T, Fukuyama S, Maehara Y, Therapeutic strategy for postoperative recurrence in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5(5):1048-1054.

- Sugimura H, Nichols FC, Yang P, et al. Survival after recurrent nonsmall-cell lung cancer after complete pulmonary resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(2):409-418.

- Starnes SL, Pathrose P, Wang J, et al. Clinical and molecular predictors of recurrence in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1606-1613. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Ramalingam S, Sandler AB. Salvage therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: factors influencing treatment selection. The Oncologist. 2006;11:655-665.

- Saisho S, Yasuda K, Maida Ai, et al. Post-recurrence survival of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer after curative resection with or without induction/adjuvant chemotherapy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;16(2):166-172.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Musikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

- Ruiz M, Reske T. Recurrent non–small-cell lung cancer in elderly patients: a case-based review of current clinical practice. Commun Oncol. 2012;9(5):165-170. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(10):2095-2103.

- Yano T, Okamoto T, Haro A, et al. Local treatment of oligometastatic recurrence in patients with resected non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2013;82(3):431-435.

- Johnson DH, Schiller JH, Bunn PA Jr. Recent clinical advances in lung cancer management [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(14):1520 ]. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(10):973-982.

- Reck M, Heigener DF, Mok T, Soria J-C, Rabe KF. Management of non-small-cell lung cancer: recent developments. Lancet. 2013;382(9893):709-719. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Updated guidelines for non-small cell lung cancer. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Yano T, Haro A, Yoshida T, et al. Prognostic impact of local treatment against postoperative oligometastases in non-small cell lung cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102(7):852-855.

- Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616-1625. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Grutters JPC, Joore MA, Wiegman EM, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients surviving non-small cell lung cancer. Thorax. 2010;65:903-907.

- Elkin EB, Bach PB. Cancer’s next frontier: addressing high and increasing costs. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1086-1087. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Sprandio JD. Oncology patient-centered medical home and accountable cancer care. Commun Oncol. 2010;7(12):565-572. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Donato R. Intracellular and extracellular roles of S100 proteins. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;60(6):540-51.